Most companies treat their website like a creative exercise.

They debate colors, layouts, and homepage headlines as if the goal is to “finish” a site that everyone likes.

That approach misses what a website actually is.

Your website is a tool. When you are not communicating one to one, it sets the narrative. It shapes perception, answers questions, and nudges decisions without you in the room.

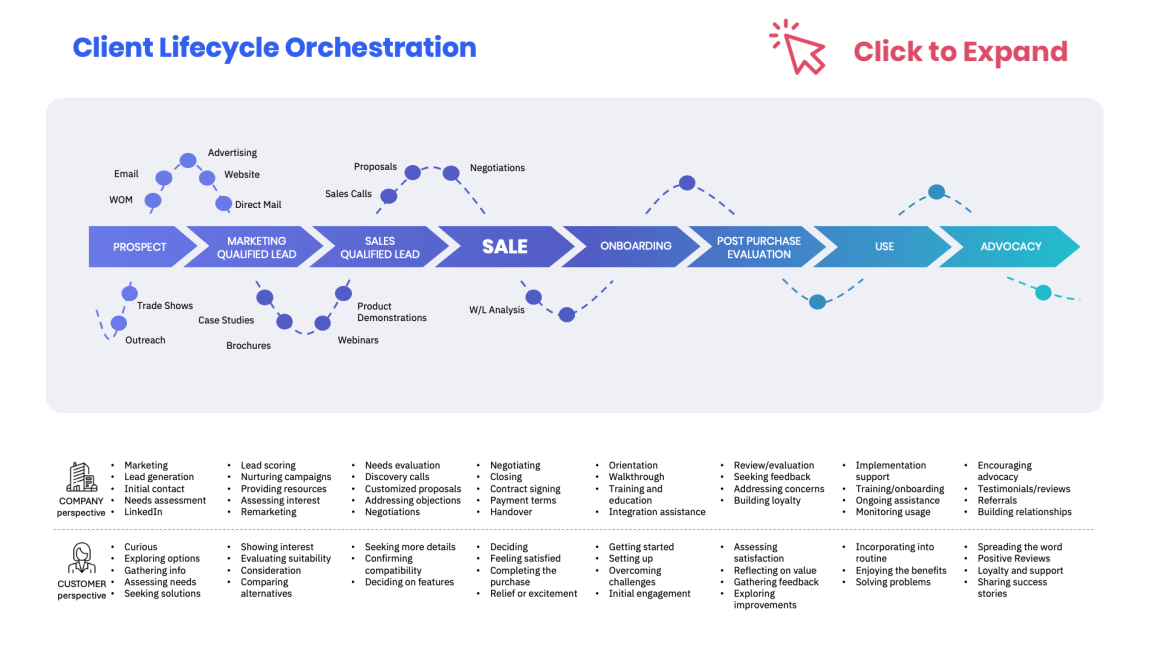

An approach to add to your planning process is to start with your client lifecycle and work backwards.

Map out the stages a buyer moves through from first awareness to signed contract to repeat work. Then list the touchpoints where they interact with you.

There are two perspectives to take when you do this.

The first is the actor. This is your company. From this view, you are focused on what needs to happen at each stage: marketing activities, sales actions, follow-ups, onboarding steps, and internal handoffs.

The second is the user. This is the customer. Here, you consider not only what they do, but what they are thinking and feeling at each stage. What questions do they have? What uncertainty are they trying to reduce? What would make the next step feel easier?

Strong websites are designed where these two perspectives overlap. They support the actions your business needs to take, while making the experience clear and reassuring for the person moving through it.

Once you do this, your website stops being “a site” and becomes a set of tools aimed at specific goals.

In almost every business, your website can play three different roles. Think of them as three camps in your toolbelt.

1. Experience design

This is about how you want someone to feel at a given touchpoint.

Not impressed. Not entertained. Clear and confident.

At early stages, experience design creates calm. It signals competence, focus, and seriousness. Later in the lifecycle, it reinforces reassurance and momentum.

A pricing page should feel straightforward and predictable. A case study should feel concrete and real. A contact page should feel easy, not like a commitment.

2. Communications

This is the information layer.

Your buyer has questions at every stage: what is this, who is it for, what does it cost, how does it work, what happens next, and what could go wrong.

The job of the website is to answer those questions in the right order, at the right time, without forcing a sales call.

If a buyer has to guess, they hesitate. If they have to ask, you create friction. If they cannot explain your offer internally, you lose.

3. Collect and apply data

This is the feedback loop.

Your website can tell you what people care about, what they ignore, where they drop off, and what prompts action.

Used properly, data turns your website into an improvement engine. It allows you to iterate based on real behavior, not internal opinion.

This might mean tracking which service pages get attention, which calls to action drive bookings, or which objections show up repeatedly.

How to apply this

Start simple.

-

Write down your client lifecycle stages in plain language.

-

List the key touchpoints for each stage.

-

Assign a goal to each touchpoint.

-

Build or adjust pages to serve that goal and fit your process.

This is where websites become more than just an online brochure. They become an integrated component of your revenue operations.

You stop arguing about taste and start designing for outcomes. A page is not good because it looks modern. It is good because it moves someone forward.

Once you build your site this way, the launch stops being the end.

Your website becomes something you actively use, refine, and aim at real business objectives over time.

That is the difference between a website that looks nice and a website that does work.